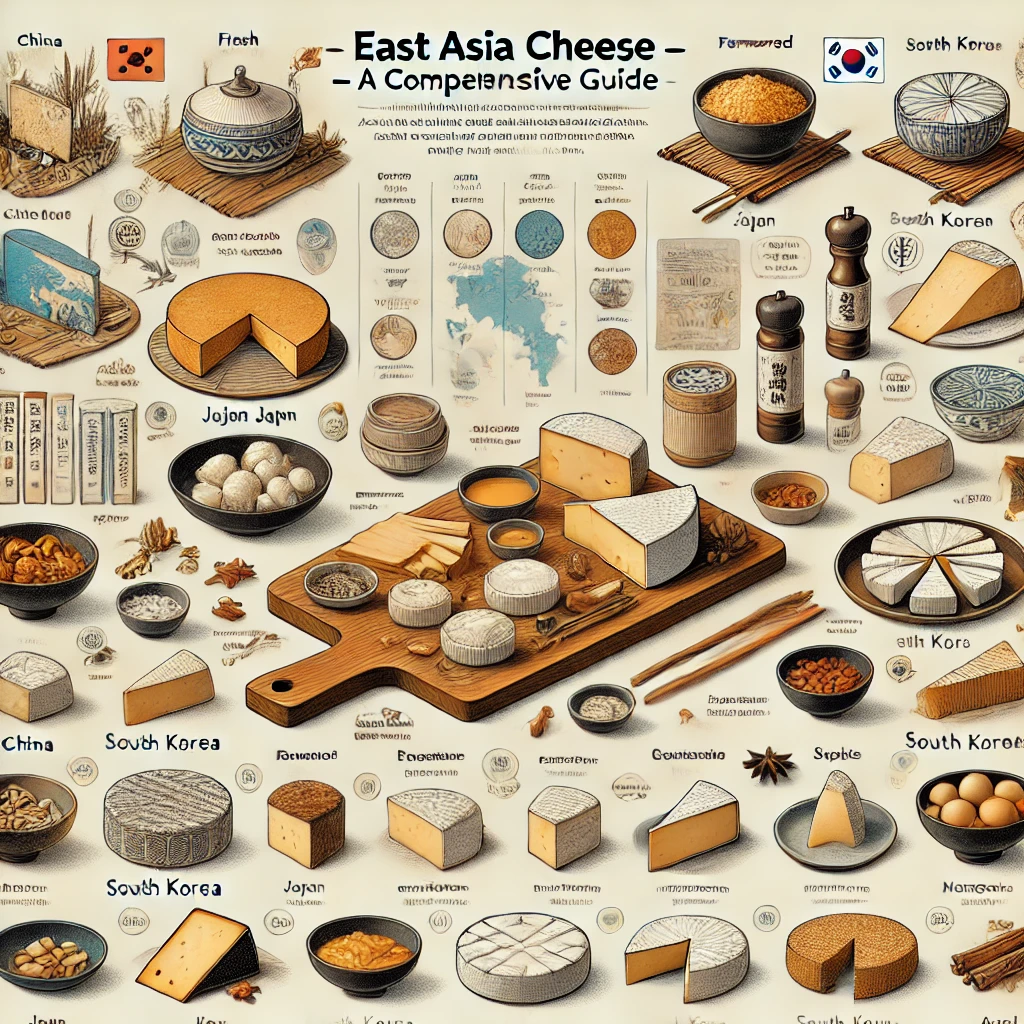

When people think of cheese culture, Europe typically takes centre stage. Yet East Asia—home to ancient fermentation crafts, soy innovations, and coastal dairy traditions—has quietly developed its own cheese identity. While dairy was not central to historical diets due to climate, livestock usage, and lactose tolerance patterns, the region today produces fresh, mild, brined, stretchy, tea-infused, and tofu-based cheese forms that reflect centuries of culinary evolution.

From stretchy Korean mozzarella-style cheese to Japan’s smooth cream cheeses and China’s traditional goat milk rubing, East Asia offers a variety of flavours blending ancestral methods with modern fusion cuisine.

This guide explores the most iconic cheeses in China, Korea, Japan, Mongolia, and Taiwan—their origins, textures, culinary uses, and how East Asian cheese culture continues to grow.

🌏 Cheese in East Asia: A Historical Background

Unlike Europe, East Asia historically did not depend on dairy, largely due to:

-

Heat and humidity slowing milk preservation

-

Agricultural prioritisation of rice, soy, and tea

-

Use of livestock primarily for labour, not dairy

-

Widespread lactose sensitivity

This led to tofu, soy curd, and fermented bean products replacing dairy in texture and nutritional function. But today, globalisation, urban coffee culture, baking trends, and food fusion have turned cheese into a mainstream flavour in East Asia.

🇨🇳 China – Ancient Herding Meets Modern Dairy

China’s cheese landscape stretches back to nomadic tribes of Yunnan, Tibet, and Inner Mongolia.

🧀 Rubing (Yunnan Goat Milk Cheese)

-

Firm, white, savoury

-

Pan-fried, grilled, or stir-fried

-

Texture similar to halloumi, but milder

Often served with chili oil, herbs, and tea salt.

🧀 Nai Lao (Beijing Milk Curd)

-

Soft custard-like cheese

-

Slightly sweet and creamy

-

Served chilled like pudding

🧀 Mongolian Byaslag

-

Hard, salty dried cheese

-

Made from yak, goat, or cow milk

In Mongolian grasslands, cheese is tied to nomadic survival—smoked, sun-dried, and preserved for long winters.

🇯🇵 Japan – Precision, Purity & Cream Cheese Mastery

Japan is East Asia’s most modern cheese producer, excelling in texture, finesse, and dairy-based desserts.

🧀 Hokkaido Soft Cheese

-

Buttery, milk-forward, mild

-

Used in pastries, buns & souffle cakes

🧀 Sakura Cheese

-

Washed in cherry blossom liqueur

-

Floral, aromatic, pale pink rind

🧀 Hokkaido Cream Cheese

Japan’s café culture relies heavily on this variety:

-

Smooth and spreadable

-

Perfect for cheesecakes, pastries, taiyaki fillings

🧀 Koji-Ripened Cheese

Using traditional fermentation moulds:

-

Creates deep umami notes

-

Comparable to miso and sake aging styles

Japan’s cheese reflects its culinary philosophy: clean taste, minimalism, precision.

🇰🇷 Korea – Street Food Melting Culture

Korean cheese is heavily driven by urban snack culture and K-food creativity.

🧀 Korean Mozzarella (Cheese-Pull Cheese)

-

Extremely stretchy

-

Used for corn dogs, hot pots, tteokbokki

🧀 Creamy String Cheese Snacks

-

Found in convenience stores

-

Mild, slightly sweet, milk-forward

🧀 Cheese Buldak, Cheese Ramyeon

Korea uses cheese as balance against spice heat:

-

Mild dairy reduces chili intensity

-

Creates fusion comfort dishes

Korean cheese fits a playful, social eating style—long cheese pulls, street grills, and fusion fast food.

🇹🇼 Taiwan – Tea Culture Meets Dairy Modernity

Taiwan blends dairy techniques with its bubble tea empire.

🧀 Cheese Foam Tea (Cheese Tea)

-

Whipped cream cheese, sea salt, sugar

-

Served atop iced tea or matcha

-

Both sweet and umami

🧀 Taiwanese Milk Cheese Toast

-

Thick, buttery, milky

-

Often topped with condensed milk

🧀 Fermented Tofu Cheese Crossover

-

Tofu preserved in brine

-

Texture and saltiness echo cheese

-

Served with congee or rice

Taiwan’s cheese tastes are driven by dessert fusion and café culture.

🇲🇳 Mongolia – Original Nomadic Dairy

Mongolia may be East Asia’s oldest cheese homeland.

🧀 Aaruul

-

Sun-dried curd

-

Hard, tangy, long-lasting

-

Survival food for horse-riding tribes

🧀 Byaslag & Tarag

-

Hard and brined, or soft fermented

-

Made from cow, yak, or camel milk

Dairy is spiritual in Mongolian culture—symbolizing hospitality, sustainability, and nomadic freedom.

🧀 Regional Cheese Styles Across East Asia

| Region | Cheese Type | Texture & Taste |

|---|---|---|

| China (Yunnan) | Rubing | Firm, grillable, mild |

| Japan (Hokkaido) | Soft & Cream | Buttery, subtle, dessert-ready |

| Korea | Stretch-Curd | Chewy, melty, ideal for spice |

| Taiwan | Cheese Foam | Whipped, salty-sweet, drink topping |

| Mongolia | Aged Nomadic Dairy | Hard, tangy, preserved |

🍽️ Cheese in East Asian Cuisine

Cheese in East Asia is not the meal—it’s the flavour enhancer.

Popular Uses

-

Street toast with cheese butter

-

Cheese-topped tteokbokki

-

Cheesecake soufflés (Japan)

-

Cheese tea (Taiwan)

-

Pan-fried rubing with chili oil (China)

Pairings

-

Green tea

-

Jasmine milk tea

-

Korean makgeolli (rice wine)

-

Umeshu (plum wine)

Unlike European boards of olives and wine, East Asia pairs cheese with tea, spice, and sweets.

🌱 Dairy-Free Cheese Evolution

Due to long-term lactose sensitivity, East Asia leads in lactose-free cheese alternatives:

-

Coconut cheese

-

Rice-milk cheese

-

Soybean curd cheese

-

Cashew milk cheese

These are not imitations but cultural continuations of tofu craft and fermentation mastery.

⭐ Final Summary

East Asia’s cheese history is less about imitation and more about innovation. Instead of Alpine caves and French rinds, the region offers:

-

tea-based cheese foams

-

grilled goat milk rubing

-

stretchy K-cheese for street snacks

-

airy Hokkaido cheesecakes

-

nomadic preserved curds

Cheese here adapts to humidity, spice, tea culture, and café lifestyles—proving that dairy, when embraced creatively, flourishes beyond tradition.

FAQs — East Asia Cheese

1. Does East Asia have traditional cheese?

Yes. China’s rubing and Mongolia’s aaruul are ancient cheese forms predating modern dairy.

2. What is cheese tea?

A Taiwanese drink topped with salted whipped cream-cheese foam, blending sweet and savoury notes.

3. Why is cheese mild in East Asia?

Temperatures and local tastes favour fresh, soft, lightly salted textures.

4. What is the most popular Japanese cheese today?

Hokkaido cream cheese used in soufflé cheesecakes and pastries.

5. How does Korea use cheese differently?

Cheese balances spice—melted over buldak, ramen, and street corn dogs.